The Battle of Bunker Hill and Dr. Joseph Warren

The first of a series of articles commemorating the 250th Anniversary of the beginnings of the American Revolution.

The Death of General Warren by John Trumbull

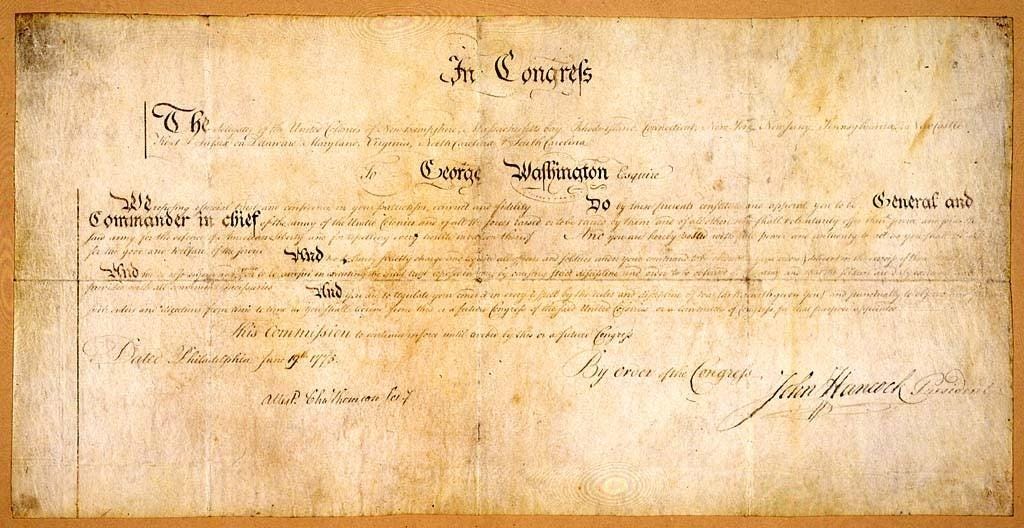

Washington’s Commission as Commander-in-Chief

The Battle of Bunker Hill and Dr. Joseph Warren

For Americans, this Spring of 2025 will mark the 250th anniversary of many of the nation’s founding events. The Battles of Lexington and Concord and the midnight rides of Dawes and Revere were celebrated on April 19. May 10 commemorated the capture of Fort Ticonderoga by Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys as well as the convening of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, with John Hancock elected as its President on May 24. On June 19, that body would appoint George Washington as commander-in-chief of the newly minted “Continental Army”.

But perhaps the most significant of those early revolutionary episodes in 1775 was the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17. The skirmishes that had preceded it were minor by comparison. The clash which took place on the Charlestown peninsula across from Boston-proper was the first real pitched battle of what neither side yet realized was becoming a full-blown war. It pitted British army regulars, considered among the most capable soldiers in the world, against a ragtag collection of inexperienced colonial militiamen. In terms of numbers of troops engaged and casualties on both sides (over 1,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded), it far exceeded the limited encounters at Lexington, Concord, and Ticonderoga.

Bunker Hill had a traumatic effect on Bostonians, New Englanders, and people throughout the colonies, struck not only by the number of killed and wounded but by the reported ferocity of the fighting. After such a bloodletting, many on both sides of the Atlantic despaired of mediating the dispute and returning to some kind of peaceful union between Great Britain and her American cousins.

Moreover, a profound impact and deep sense of loss were keenly felt by the pro-rebel citizens of Boston and Massachusetts upon learning of the death of Dr. Joseph Warren, killed in action during the battle.

There are many names which come down to us in our history from the Revolution: Washington, Jefferson, Adams, Lafayette. But no name loomed larger among the early leaders of the Revolution than Joseph Warren. A brilliant young physician, aged 34, Warren had emerged as the most charismatic and inspiring of the Sons of Liberty, the organization formed in and around Boston in 1765 in opposition to the Stamp Act imposed on the colonies by the British Parliament.

That group included such notables as merchant John Hancock, lawyer James Otis, maltster (but not really a brewer) Sam Adams, and inventor and publisher Benjamin Franklin. They had organized and carried out boycotts, protests, and the forever famous Tea Party in 1773. As Boston and Massachusetts moved closer to militating for outright independence from Great Britain in 1774, the “Sons” and other supporters of separation formed the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to provide for the administration of local government in the colony and to support and promote the move to independence. When its first president, John Hancock, departed for Philadelphia to head up the Second Continental Congress in 1775, Dr. Warren was elected to succeed him.

Warren directed many of the activities of the Sons in the weeks and months leading up to the commencement of hostilities at Lexington and Concord, employing complex and clever tactics designed to provide the colonials with extensive intelligence as to British troop movements, armaments and supplies. He devised the plan to coordinate several riders to sound the alarm among the towns and villages west of Boston once the redcoats began to march there in search of colonial weapons caches and possibly prominent rebel leaders.

His contribution to the “American” cause in those early days was singular. Appreciation of his talents, first medical and then political and military, were expressed as much by British commanders and officials as by the revolutionaries. General Thomas Gage, the Royal Governor of Massachusetts at that time, is quoted as saying that Joseph Warren’s death was equal to the deaths of 500 ordinary colonials. Similarly, Thomas Hutchinson, the former Royal Governor preceding Gage, opined “… if he had lived [Warren] bid as fair as any man to advance himself to the summit of the political as well as military affairs and to become the Cromwell of North America.” Peter Oliver, the former Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, delivered perhaps the highest praise some years later in proclaiming that if the young leader had lived, “Washington would have remained in obscurity”.

A harsh legend, often omitted from young Americans’ history texts, but which brutally signifies the hateful regard in which the British soldiers held the man who for months had organized a violent and costly resistance against them, is that of their mistreatment of Warren’s corpse once discovered among the many dead bodies littering the battlefield after the fighting was over and the colonials had fled. For days it was reportedly bayoneted, spat upon, and desecrated, thrown into a mass grave, exhumed, abused some more, and possibly beheaded before being reburied. Finally, in April 1776, after the British had evacuated Boston, Paul Revere and Warren’s two brothers located his remains on the battlefield and transferred him first to the Old Granary Burying Ground in downtown Boston where many of the early patriots still rest before removing him to his final burial place in the family vault at Forest Hills Cemetery in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston. It is said that Warren’s badly mutilated corpse was only positively identified by Revere, a silver and copper smith by trade, who recognized a false tooth he had fashioned for the young doctor.

The Patriots’ respect and admiration for Warren was manifested many times and in many ways in the years following his premature demise. One of the earliest examples came with the founding and naming in Pennsylvania of Warren Township and the surrounding county of Warren in 1795. A veteran of the Revolution, William Irvine, an Irish immigrant who had settled in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and risen to the rank of Brigadier General under Washington, was tasked to survey and layout the lands along his state’s western frontier. Originally a trained physician who had served as a ship’s surgeon in the British Royal Navy before becoming a devotee of the American Revolution and joining that cause, Irvine named the first town and county he laid out for the fellow physician, patriot, and warrior whom he greatly admired.

Today, there are numerous towns, villages, and counties named for Warren and many parks, monuments, and statues dedicated to him. Then, in 1775, and in 1795, and still today, the ties that bound us together were for the most part not ethnic, not racial, not religious, not geographic, and not class based, unlike almost every civilization that preceded us. Then, as now, a large cross-section of the population was from somewhere other than the 13 colonies strung along the New World’s eastern seaboard. We were joined in a state of mind. There were great nuances and outright differences within that overall state of mind but a definite shared commitment to a new way of life, a new social contract, an idea of self-reliance and self-governance, and the possibility of liberty, prosperity and safety that just wasn’t broadly available in Old Europe anymore for most ordinary people.

The light of that commitment burned brightly during the Revolution itself and for the generation that followed. Certain citizens of Litchfield County, CT, named their village “Washington” … in 1779! They were the first to do so, years before the nation’s capital or any other place was so named. The Revolution was not yet close to being won and the good General was far from being envisaged as the “Father of Our Country” or our first president. But the yeoman farmers, merchants, and shopkeepers of southern New England expressed solidarity with the aristocratic Virginia planter on whose shoulders rested all their shared hopes and dreams, despite the risk of British and Loyalist retaliation for their choice of name.

As Brigadier Irvine surveyed his beloved, adopted Pennsylvania’s western frontier in the 1790’s, and considered the mysteries of what lay beyond, he endowed the new rural township and surrounding county with the memory and the spirit, patriotism, and foresightedness of a not so distant, Harvard-educated, Boston physician who had also glimpsed the figurative frontiers presented to colonial America and devoted his considerable intellect, integrity, hard work, and ultimately his life so Americans could reach them.

200 years ago, the Marquis de Lafayette concluded his farewell tour of the United States in September, 1825, after a monumental 13-month long stay in which he visited all of the then 24 states in the Union and dined with all 3 former Presidents still living (Adams, Jefferson, Madison), the 2 Presidents in office during his trip (Monroe, Quincy Adams), and 2 future Presidents (Jackson, Harrison). During those mostly private encounters with the young nation’s leaders, Lafayette strongly urged them, and through them all Americans, to hang onto the “Era of Good Feeling” as our first years of nationhood came to be called. He had seen after his return to France and Europe following the American Revolution how his native country and the entire continent had devolved into a violent, strife-torn land where the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and vicious ethnic and religious conflicts had soaked one country after another in blood and lasting enmity.

He knew well that his cherished United States, which had largely escaped such horrors, was beginning to experience critical differences over slavery and its expansion into the territories, between the largely agricultural south and increasingly industrial north, and among the body politic as the advent of Jacksonian democracy shifted some political power from the more wealthy, conservative Federalist establishment to the common people. Each of the past, present and future Presidents remarked on the wisdom and truth of Lafayette’s urgings in their writings and speeches. Many of the reporters, academics, officials and regular folks to whom he made his plea throughout his journey also echoed his sentiments.

The spirit of ‘75, which became the “Spirit of ‘76”, was alive and well in Brigadier Irvine and the Pennsylvania frontier people in 1795 as it was still in General Lafayette and many Americans in 1825. A spirit which held forth the promise of what Lincoln would later call “a new birth of freedom”. That spirit and that promise would be sorely tested down through the generations to follow. But never extinguished, never abandoned, despite civil war and social turmoil at home and world wars abroad which threatened to engulf us too. It was a spirit that would come to inform “American Exceptionalism”, a term which people define in varying terms but which surely means that our country is unique and exemplifies a commitment to democracy and freedom as well as some responsibility to stand for and spread those ideals around the globe.

An Italian friend traveling in the United States once remarked to me how many American flags she observed wherever she went, flying proudly not only from government and military sites but from private homes and town squares, and how that was not broadly so in Italy or most European countries. I ventured that whereas her native Italy had millenia of shared Roman Catholic religion, an ancient and shared language, customs, and traditions, the United States had none of those. Our patriotism was and is our secular religion, our commitment to a sense of ourselves as fair, just, welcoming, and free was and is our guiding social custom and tradition.

Joseph Warren was an early martyr to that secular religion. And now, we once again find ourselves navigating a time of strained and even ill feelings among our citizenry. As we do, let’s hope that the spirit that still explains why we have a Warren, Pennsylvania, a Warren County, Virginia, a Lafayette, Louisiana, and, yes, a Washington, Connecticut, as well as countless national flags of all shapes and sizes waving in the breeze from coast to coast, will regain its luster. As Lincoln hoped for our beleaguered nation in his First Inaugural Address delivered on the eve of civil war: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Amen.

Jacj, I think I enjoyed your comments as much as you enjoyed the article! Thanks for the encouragement, old pal. And it's the first of a series of articles wherein I'll revisit many of the subjects. And will be happy to include the RL connection for Dr. Warren, who was I believe a master there as well as an alum!

Nice work, Dino! I'm a bit ashamed to say I did not know of Dr. Warren. High praise indeed that the British thought so much of him. And I've just got to add that our old friend Billy "the duck" Donley worked for a time at GM in Warren, Ohio!